In Conversation with Jeanne Gang

Harvard GSD Alumni Shovan Shah (MAUD ‘20) interviews world renowned architect and urban designer Jeanne Gang about her career, firm and future of Studio Gang.

Architect Jeanne Gang (she/her), FAIA, is the founding principal and partner of Studio Gang. Her inquisitive, forward-looking approach to design—unique in its pursuit of new technical and material possibilities as well as in its expansion of the active role of designers in society—has distinguished her as a leading architect of her generation.

Edited on August 10th 2023

Shovan Shah (SS):

Can you talk about an important project you worked on prior to Studio Gang? How does it relate to your personal work and what do you think about it now?

Jeanne Gang (JG):

I worked for two offices before I started my own firm;, one was OMA in the Netherlands, where I worked on two projects in France. Then, in the States, I worked for Booth Hansen in Chicago. An important early experience in my career was leading the design for a house in Bordeaux [Maison à Bordeaux] and collaborating with Rem Koolhaas. I was very interested in the site and came to care about the people who would be living there. I felt how important it was to accommodate their needs and understand what they truly wanted. At the same time, I got the experience of coordinating closely with the structural engineers from the very beginning. I’ve always enjoyed working directly with consultants like engineers, lighting designers, and artists – especially when it is collaborative. Engineers are often my closest collaborators. On that particular project, I remember walking the site with Cecil Balmond from Arup and listening to his observations first-hand.

SS:

What do you carry forward from these early experiences into projects at Studio Gang? Are there any influences we can trace back to in your designs?

JG:

One of the main practices I carried forward from this time was, like I just said, the process of working closely with consultants and experts early on in a project. I believe that anyone on a project team can have a valuable observation, but as a designer you have to be open to hearing what consultants and experts have to say, and then seeing how you can make use of it to evolve the design.

I think another take-away was applying a critical lens to the work—like we do at the GSD. You can see that approach in our work at Studio Gang. We don’t just make form; we are trying to get to the essence of a project. I think it is important to learn a lot about a project before jumping into form-making, so there is also a research methodology that we use. This is not an outgrowth of something I saw in other offices, but rather the result of having a deep personal curiosity in everything. That goes for others in my office as well.

In terms of design, I’d say that our work developed into something that is distinctly different from my early experiences in other offices. Having said that, I wouldn’t be who I am without these experiences, and I am deeply grateful for them.

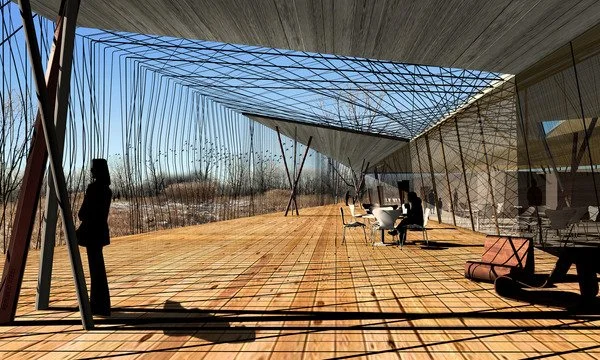

An early Studio Gang project highlights our distinct set of interests: In 2004, we won an international competition for the Ford Calumet Environmental Center . This was an environmental, education, exhibition, and job-training center on the far Southeast Side of Chicago. After winning, we took this project all the way to construction documents, but it was never built for a variety of externalities. Nevertheless, it yielded productive lines of inquiry about sustainability and reuse that are still being advanced in our practice today. Our approach was to reimagine design using only the materials that were abundant, available, and near to the site—similar to how a bird would build a nest—thus reducing energy-use and embodied carbon in the building. As the site was in a former industrial area, this meant using materials like steel harvested from former buildings, or slag, a byproduct of steel production. We figured out what it would take to do that—to start with what was there.

Another distinction between the practice I created and my previous office experiences is my attention to ecology. At the Ford Calumet site, I saw the importance of protecting the surprising profusion of wildlife that was located along this migratory flyway. Our research led us to discover a big problem for migratory birds who encounter cities and buildings along the waterways they use to navigate their journey. Glass is hard for birds to see and their collisions with it can be fatal. The numbers are shocking—close to a billion birds annually—making buildings one of the largest causes of avian mortality. We knew we had to do something to address this threat. We chose to collaborate with an ornithology and conservation biology professor, Dan Klem, who had done some of the most extensive research on the topic at the time. We learned and discovered a lot about this problem ourselves and how to prevent it through design. Since then, we’ve continued to work on bird safety for buildings and advocate for policy that will help reduce this threat to biodiversity.

In those ways, Ford Calumet was a precursor to many important ideas and values that our Studio holds today: recycling and reuse, bird safety, carbon neutrality, sensitivity to the ecology of a site, and connecting people and nature.

Image © Studio Gang

SS:

“Fuck Context" is a phrase famously attributed to Rem. What would you say to that?

JG:

I think his quote has been taken out of context. That said, I don't agree with the sentiment at all because “tabula rasa” is not where we need to be going right now in terms of our environment. We should be reducing carbon emissions, period.

Like I mentioned earlier, our informal motto at the Studio is “start with what's there.” I’m sure you’ve heard it dozens of times working here at the office, Shovan! Context is obviously all about what is already there. That’s not to say we mimic or “reproduce” context or historic architecture. But we do try to develop an understanding of a place. We try to build on a place’s existing positive qualities. And that also means reusing buildings as much as possible: reusing their foundations, working with nature-based solutions, and not subscribing to the idea that everything must be torn down. New ideas can creatively emerge from what already exists. We're in a very critical time for the environment, so I hope my motto of “starting with what's there” can be a kind of the antidote to capitalism’s old call for creative destruction.

SS:

How do aspects of real estate development and social impact work themselves out within a project?

JG:

It’s really very important to find developers that you like to work with and to get on the same page with them early on about what the design can be. On a project like Assemble Chicago, our winning proposal for C40’s Reinventing Cities competition, we were completely aligned the developer, The Community Builders. They wanted to achieve something environmentally and socially meaningful, and that's exactly what our competition entry achieved. I really like the example of C40 because the brief plainly stated: “How do we create social equity and sustainability?” All of the projects that are a part of C40, which is global network of cities trying confront the climate crisis, learn from each other. It's a way of sharing knowledge and ideas that are desperately needed to meet the challenges of the climate crisis.

Image by Aesthetica Studio © Studio Gang

SS:

What if it isn’t a competition?

JG:

Often, it's not an all-out competition. We might be approached by a developer who says, “We already have this land, we want to do this project, and we want to work with you.” Either way, whether competition or direct commission, I think it can be the architect who initiates ideas about community engagement. As architects, I think we understand (or should understand) the importance of making sure a development considers those who live nearby and thinking about opportunities that bring benefits to adjacent communities. We've successfully collaborated with developers on different processes for engaging with communities. For example, we worked with our client, Westbank, on a project called Arbor in San Jose. It is an office tower that connects inhabitants to the region’s rich ecology. We organized a Youth Design Leadership group for high school students that lived near the project area. Over the course of seven weeks, in a studio format, we shared design tools that the students could use to express their ideas for the future of their downtown in San Jose. Westbank supported this work and exhibited their projects.

To achieve meaningful change—whether it’s increasing equity in a city or minimizing a project’s impact on the climate—we have to share our knowledge widely, not only with other architects, but with our clients and the larger community as well. It’s less about the architect showing off a rendering and simply informing people about what is to come. It should instead be a reciprocal process between these different actors.

Many people associate our early work with large projects like Aqua Tower, but we actually started out doing smaller community projects, and we still do these because they matter. I’ve already spoken about the Ford Calumet Environmental Center, but when I first began my practice, my projects were in different neighborhoods like Chinatown and Auburn Gresham. Chicago is a mosaic of neighborhoods. By designing these different projects early in my career and working with people, listening to their stories, and finding out what was important to them, I got to know the city very intimately. Today, my team and I still connect with the people who will inhabit the buildings we design. We still think about all of our projects as serving communities.

Jeanne Gang, "Will technology save us?" Domus, ed. David Chipperfield, issue 1050, October 2020.

Image by Aesthetica Studio © Studio Gang

Image by Aesthetica Studio © Studio Gang

SS:

Where do you see yourself in Chicago's architecture and architectural history?

JG:

In Chicago, modern architecture places a strong emphasis on how a building is made, and what it is made of. When you look at Chicago architecture, you can see how Mies’ buildings emphasize steel, or how Bertrand Goldberg’s buildings emphasize concrete. We fit into this tradition of an almost Bauhaus-like approach to materiality, letting the material qualities be expressed.

Your question is difficult to answer, though, because I don’t spend much time thinking about my position in architecture history. When we speak about architectural history the discussion tends to move toward style because that’s how historians often classify buildings. But when I’m working in the moment, I’m thinking about opportunities, about discovering things, about making the project the best it can be and about being true to the idea. We don’t talk about style at all, really. I see architecture as constructing relationships. It sets the stage for people to interact with each other and the place. If there is subtle cohesion between our works, it’s due to a sensibility that becomes visible, perhaps because of our design process. I‘ll give an example: Aqua Tower and the Pavilion at Lincoln Park Zoo. Though they don’t look alike, they share some common design threads. They are connecting people to each other and to their environment. At Aqua, this happens through the balconies that allow people to see each other and connect to the city. At Lincoln Park Zoo, this happens through the flexibility of the public space set in a rewilded urban nature. They both innovate with materiality—highlighting their material’s inherent qualities. For us, the aesthetic has to be functional and offer additional benefits. You can find those aspects in many of our projects.

Image by Steven Hall © Studio Gang

Image by Steven Hall © Studio Gang

SS:

What is important to you going forward with projects for Studio Gang?

JG:

We want our work to be good for the planet and keep achieving better results on this front, Part of that means finding like-minded clients and collaborators that are equally energized to address the big challenges. We will look to continue reducing carbon and continue to increase biodiversity with our work. We want our work to serve society equitably so we will continue to select projects thoughtfully and evolve our engagement work with communities. It is important to me to keep an experimental approach and keep discovering and learning. Over time, different typologies will emerge or hybridize and that will call for innovation so we always will want to be part of that design conversation. Ultimately, research will continue to be important. and we will keep expanding that aspect of our practice.

We have a number of exciting recently completed and upcoming projects that span different building types and complexities, like the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, which is the latest addition to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and the United States Embassy in Brasília. These projects and our future projects use design to help organizations move into the future.

Image by Iwan Baan © Studio Gang

Image by Iwan Baan © Studio Gang

We also continue to pursue projects that reimagine existing buildings, like the Beloit College Powerhouse, an old coal burning power plant that we transformed into a student union centered on recreation and wellness. Projects like this are important in both their reduction of embodied carbon and the way they activate urban environments. At the GSD, my Research and Options studios for the last six years have been centered on reimagining existing concrete structures to advance the language and knowledge around reuse as a design strategy.

Image by Tom Harris Photography © Studio Gang

SS:

What is Studio Gang’s approach to urban scale projects?

JG:

I think of our urban projects as setting cities up for change at different rates according to what they are ready to implement. There are the fast “get-it-done” projects, the medium-term plans that span, say, five to ten years, and the long-term strategic plans, which are more like guiding principles for future architects. Some of our urban projects are very visible and change the face of the city while others might just change the way existing assets are used.

We are very interested in cities on rivers. Our research on the Chicago River gave rise to our publication Reverse Effect: Renewing Chicago's Waterways (2011), and eventually, to our two public boathouses on the river: the WMS Boathouse at Clark Park in 2013 and the Eleanor Boathouse at Park 571 in 2016. Both near-term and medium-term activations are embodied by the boathouses, which have been an essential part of reviving the riverfront both ecologically and recreationally. I would even say that the longer-term goal of changing people’s perceptions of the Chicago River has now been achieved. But even though our very high ambition—to un-reverse the Chicago River—may still be way out in the future, judging by the progress that has already been made, it shouldn’t be called just a pipe dream.

Image © Studio Gang

Image by ©SCAPE and TyCole © Studio Gang

SS:

If you could go back to school, what skills would you learn?

JG:

I feel like I am always still learning, and I love that. If I was going back to school full time, I don’t know if I would focus on skills; those are easy enough to hone elsewhere. There is also a difference between learning and understanding which I think is even more important. But if I were going back to being a student, I would be interested in interdisciplinary projects. Working across disciplines is a sure way to increase impact and make valuable discoveries. We are lucky to have several disciplines right within the GSD and beyond that there are many other potentially fruitful projects to undertake with others in the greater Harvard community. It is important to go deep in one’s own discipline, but in challenging times like these, I think that key advancements will have to come from these collaborations.