Visualizing Wakanda:

Urban Innovation through Speculative Design

Fiona Kenney and Vaissnavi Shukl (MDes HPDM ‘20)

Image 1: Streets of the Golden City bustling with new-age trotros as shops display traditional African baskets. (© Marvel Studios)

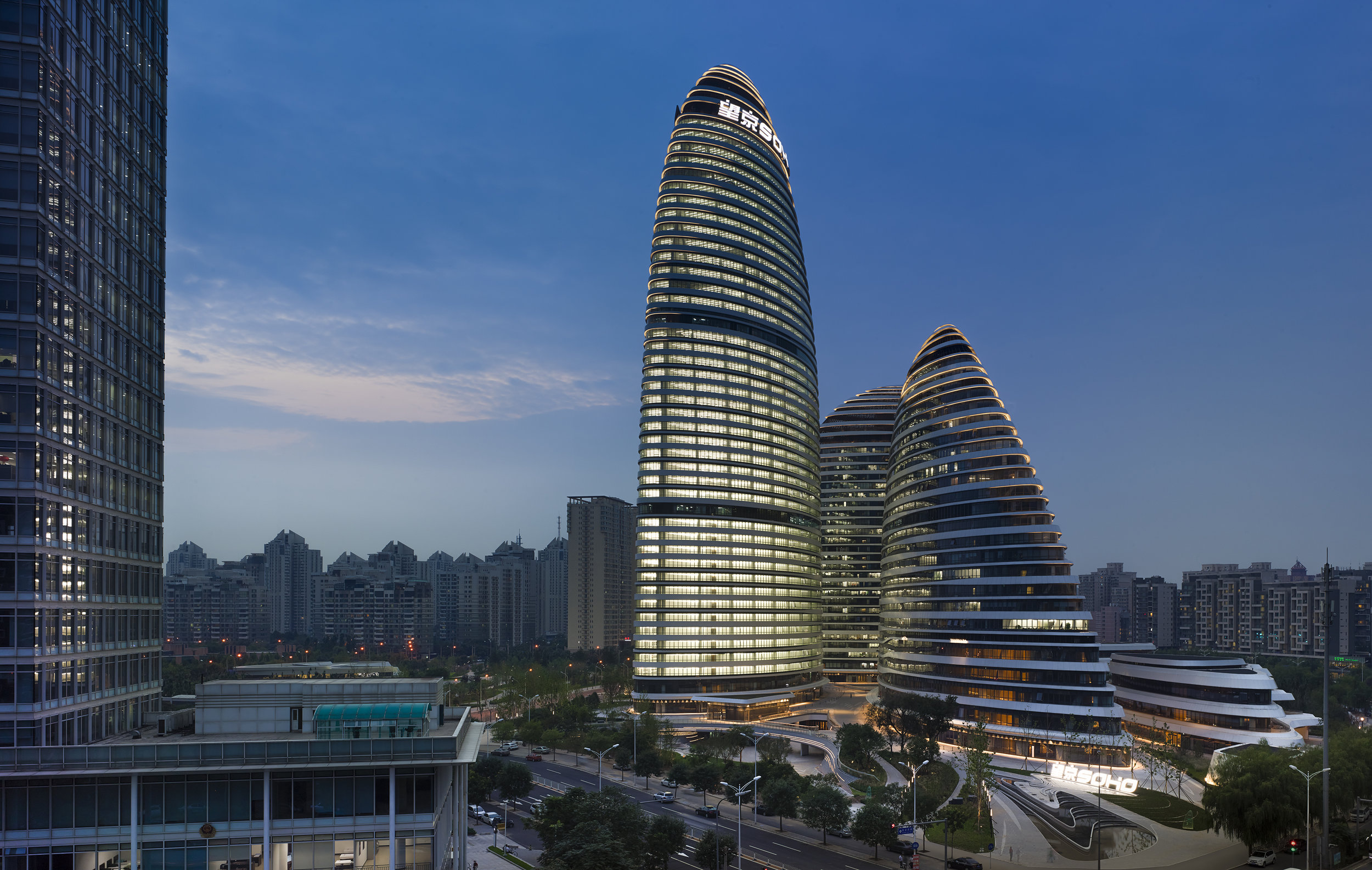

Image 2: Zaha Hadid’s Wangjing SOHO in Beijing.(Photograph by Virgile Simon Bertrand, used with permission of Zaha Hadid Architects)

Image 3: Wakanda’s Golden City (© Marvel Studios)

Urban design has long histories of enmeshment with utopian ideation—from Ledoux’s Saltworks to the City Beautiful movement, design is a demonstrated tool in speculating, generating, and enacting utopianism. Designing for fiction requires reflexivity: inspiration must be drawn to some degree from an abstraction of real-world observation. We argue that this generates an opportunity for contribution to the design disciplines by way of speculation. The ideation of fictional utopias facilitates place-making for and inclusion of people often excluded by the architectural project. The participation of non-architects in the creation of utopias generates ideas and learning for mainstream architecture and planning. In this sense, the process of fiction creation mitigates exclusivity and eliminates architecture’s barriers to participation.

Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, credited for popularizing speculative design, state that the idea of utopia is far more interesting when used as a stimulus to keep idealism alive—not as something to try to make real but as a reminder of the possibility of alternatives, as somewhere to aim for rather than build (2013). Thinking of architecture as having utopian potential is a more productive way to consider how utopia could enrich architecture (Coleman 2014). This thinking becomes a framework rather than an aspirational final product; grounding aspiration in speculative design strategies allows for possible futures to be imagined and large-scale solutions to be considered for fundamental societal challenges.

We propose Wakanda, fictional country home to the Black Panther, as a successful utopian project by way of its role in generating dialogue on urban design, good governance, heritage conservation, and sustainable design. Without any formal training in architecture or city planning, Hannah Beachler created Wakanda, playing an elemental role in shaping new discourse on what architects and planners can learn from fictional cities. Though utopian in nature, Wakanda is not detached from its real-world socio-temporal context; Beachler actively recognizes contemporary issues and presents a critique of present-day social and spatial problems.

Transportation forms an integral part of Wakanda’s capital. The portrayal of the Golden City’s transit systems utilizes aspirational, futuristic technology to solve problems of urban mobility. This emphasis on sustainability and reliance on technology to represent an ideal future is a typical pursuit of the futuristic design process. Wakanda, however, stands out by integrating technology with tradition; its buses are technologically upgraded and retrofitted while retaining their original character (Image 1). These buses, colloquially called trotros, exist even today in several African countries. In a recent interview, Beachler (2018) says, “The Wakandans didn’t just chuck that idea [of the ‘trotros’]... They took the bus, and said, ‘how do we make it so we’re not letting off emissions?...So we took the bus and kept tradition over technology.”

A human-centric approach is evident in Beachler’s design process: she created the ‘Wakanda Bible,’ a 500-page ethnographic document, which became a cardinal charter for everything Wakandan: its people, their ancestry, culture, as well as the city and its buildings. Beachler’s anthropological approach peaks during the materialization of human-centered programs into buildings well ingrained within the city fabric, such as the Records Hall. According to Toldson (2018), many conclude that Black progress is reserved for fiction; even then, the process of utopia creation gives agency to its designer to invent new, unprecedented building programs which make possible the inclusion of groups otherwise oppressed by city planning in real life.

In the pursuit of an Afro-futurist utopia, Beachler draws inspiration from the architecture of Zaha Hadid. Two of Hadid’s projects: the DDP Building, Seoul and the Wangjing SOHO, Beijing (Image 2), became primary references (Image 3). The choice of Hadid’s work as primary inspiration is not only a matter of futuristic, utopian representation but also of cultural reappropriation towards an Afro-futurist aesthetic. Beachler adopts Hadid’s forms, infusing them with traditional African elements: earthy tones on building exteriors, thatched roofs in houses made of mud and bamboo, and earthen streets lined with shops selling woven African straw baskets. Such design decisions ensure that architecture is not limited to form-making; there is emphasis on the importance of architectural gestures which situate the project within a broader historical and socio-cultural context.

The Afro-futurist movement, revived through Black Panther and derived from a combination of historical and contemporary references, is beginning to influence new discourse in planning and architecture. Whether it is aspiring for transit-friendly, walkable cities without cars (Kuntzman, 2018), or community organizing (Lessons from Wakanda: What Black Panther Raises for Black Organizing, n.d.), there are plenty of notes to be taken from Wakanda. Beachler was inspired by Hadid’s architecture; Hadid, in turn, was influenced by Russian Constructivist architects and artists such as Tatlin, Rodchenko and Chernikhov.

The cyclical process of utopian ideation is dependent on each actor improvising while designing; while the nature of change driven by architects is more form-based, designers trained outside the conventional fields of architecture and urban planning are often able to instill a strong social program in their fictional worlds. The success of Wakanda relies on the intertwining of its social project with its architectural project; any attempt to divorce one from another would have lessened its impact. Architecture has historically had to assert its independence from adjacent fields like science, fine art, and engineering: the key to radical design innovation and societal problem solving, though, may now lie at the collaborative intersections made real by works of fiction.

Bibliography:

AbdUllaha, A., Saidb, I.B., & Ossena, D. R. (2016). Zaha Hadid Strategy of Design. Sains Humanika. 10.13140/RG.2.1.3940.0083.

AtlanticLIVE. (2018). Black Panther Production Designer Hannah Beachler at CityLab Detroit [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ABg5ogMey7I.

Black Panther. (2018, September 04). Retrieved from https://www.netflix.com/watch/80201906?trackId=13752289&tctx=0,0,898b24da-264f-45c1-9a6c-db9268f69514-50524262.

Coleman, N. (2014). The Problematic of Architecture and Utopia. Utopian Studies, 25(1), 1-22.

Desowitz, B. (2018). 'Black Panther': Building Wakanda on Ryan Coogler's Vision

of Identity and Unity. Retrieved from https://www.indiewire.com/2018/12/black-panther-production-design-wakanda-ryan-coogler-oscars-1202026404/.Dunne, A. & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Flatow, N. (2018). Why We Loved Wakanda's Golden City So Much. Retrieved from https://www.citylab.com/life/2018/11/black-panther-wakanda-golden-city-hannah-beachler-interview/574420/.

Hadid, Z. (2017). Reflections on Zaha Hadid (1950 - 2016). London: Serpentine Gallery.

Hannah Beachler. (2019). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Beachler.

Harvard GSD. (2018). Rouse Visiting Artist Lecture: Hannah Beachler with Jacqueline Stewart [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAYzDzeZuG8.

IMDB. (n.d.). Lebbeus Woods (1940-2012). Retrieved from https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0940680/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1.

Kuntzman, G. (2018). Another reason to love "Black Panther"? There are no cars in Wakanda. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/black-panther-succeeds-urban-utopia-no-cars-wakanda-816212.

Lessons from Wakanda: What Black Panther Raises for Black Organizing. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://highergroundstrategies.net/lessons-from-wakanda-what-black-panther-raises-for-black-organizing/.

Montavon, M., Steemers, K., Cheng, V., & Compagnon, R. (2006). ‘La Ville Radieuse’ by Le Corbusier once again a case study. Proceedings from PLEA ‘06: The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture. Geneva, Switzerland.

Sow, M., & Sy, A. (2018). Lessons from Marvel's Black Panther: Natural resource management and increased openness in Africa. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2018/02/23/lessons-from-marvels-black-panther-natural-resource-management-and-regional-collaboration-in-africa/.

Tafuri, M. (1976). Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Toldson, I. A. (2018). In Search of Wakanda: Lifting the Cloak of White Objectivity to Reveal a Powerful Black Nation Hidden in Plain Sight (Editor’s Commentary). The Journal of Negro Education, 87(1), 1-3.

Wangjing SOHO - Architecture - Zaha Hadid Architects. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.zaha-hadid.com/architecture/wangjing-soho/

Yalcinkaya, G. (2019). Black Panther film sets are influenced by Zaha Hadid, says designer. Retrieved from https://www.dezeen.com/2018/03/01/black-panther-film-designer-zaha-hadid/.